Key points:

- People say debt was low and stable until the 1980s when financialization arose and suddenly increased the debt-to-GDP ratio.

- But inflation affects debt and GDP in ways that reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. The great inflation severely reduced debt-to-GDP between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s. Paul Volcker and the disinflation of the early 1980s are the true sources of the sudden increase in the ratio after 1980.

- Financialization did not arise in the 1980s. It has been with us at least since the 1960s. To de-financialize the economy it will be necessary to reverse, revise, or eliminate not only policies created since 1980, but also many policies created before 1980.

"Financialization revisited: the economics and political economy of the vampire squid economy" by Thomas Palley.

This is my one complaint: Thomas Palley cannot see anything

before 1980. He refuses to look. For example, he refers to the "era of

neoliberalism (1980 – today)". Financialization also began in

1980, he says:

The first stage corresponds to the period 1980 – 2008. The second stage corresponds to 2009 – today.

His definition:

“financialization

corresponds to financial neoliberalism which is characterized by the

domination of the macro economy and economic policy by financial sector

interests.”

This definition, he says,

identifies

financialization with the period 1980 – today, which distances it from

the history of financial deepening and increased financial

sophistication.

Palley expands on that thought in footnote 1:

Graebner

(2005) has shown civilization is marked by the increased use and

presence of finance. Prompted by that, Sawyer (2013, p.6 cited in

Epstein 2015, p.5) asks whether financialization has been on-going

throughout most of the history of civilization. This paper would

definitively answer “No” to that question.

Definitively: "with absolute certainty."

Palley

rejects the idea that financialization may have existed before 1980.

With absolute certainty and the shortest of answers, he dismisses the

possibility. For Thomas Palley, financialization began in 1980 by

definition. End of story.

I can see that Palley defines

financialization as having started in 1980. I can see that he is

obligated therefore to provide an unequivocal "No" to the question in

the footnote.

What I don't see is evidence. I see only insistence.

“ Evidence ”

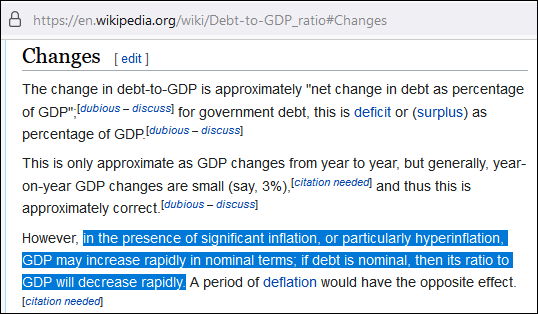

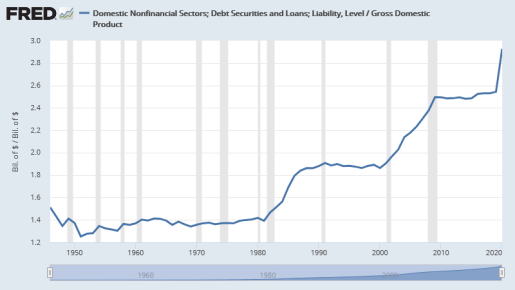

Palley offers unsatisfactory evidence. "Prior to 1980," he says on

page 31, "the domestic non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio was stable" --

and after 1980, it was not. But that is only more or less true:

His

statement ties in with the idea that the rising level of debt is

evidence of financialization. As he says in the Abstract:

"financialization rotates through the economy loading sector balance

sheets with debt."

For Palley, rising debt is evidence of

financialization. From this, it follows that a low level of debt indicates the

absence of financialization. And that, perhaps, is how Palley arrives at

the idea that financialization began in 1980. And yet, the FRED graph shows rising debt all through the 1950s.

Palley doesn't consider the 1950s. The number sequence 195 does not even exist in the PDF. Nor does the PDF show a graph of domestic non-financial debt to GDP. Instead, Palley writes:

Table 1 shows sector debt-to-GDP ratios for selected years and provides evidence ...

Table

1 shows seven years of data: 1960, 1969, 1980, 1990, 2001, 2007, and

2019. Seven years scattered across six decades. Palley presents data for seven

years out of 60, and calls it evidence.

Palley's seven data points

take us back only to 1960. He provides no evidence regarding the 1950s

-- evidence, such as it

is. Palley ignores the decade-long increase of debt-to-GDP in the 1950s,

and insists that financialization -- rising debt -- did not exist before 1980.

It just

doesn't make sense. The ramping-up of debt in the 1950s

contradicts any claim of stability before the 1960s; therefore it

contradicts Palley's claim of stability before 1980.

But was the increase of the 1950s significant, really?

Yes. Graph #1 has debt-to-GDP at 1.25 in 1951 and 1.4 in 1961.

That's a 12% increase in 10 years. If we got a 12% increase every time

10 years went by, in 2021 our debt-to-GDP ratio would have been 2.76,

about halfway up the covid increase of 2020, upper right on the

graph. You have a calculator. Check my numbers.

The debt-to-GDP increase of the 1950s was most significant. If

the 1950s rate of increase had continued, debt today

would be little different from the debt we ended up with.

If an increase

in domestic non-financial debt-to-GDP is evidence of

financialization, then the evidence shows financialization in the 1950s. This definitively contradicts Thomas Palley.

And not only Thomas Palley. In the 2011 paper The real effects of debt, Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli (page 6) write:

It is

sufficient, however, to look back at the history of the United States

(for which long back data are easily available) to understand how

extraordinary the developments over the last 30 years [1980-2010] have

been. As Graph 2 shows, the US non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio was

steady at around 150% from the early 1950s until the mid-1980s.

The

authors generously allow the reader to make an eyeball estimate to

confirm that the graph shows debt-to-GDP steady in the 1950s,

based on this disproportionately wide graph:

The

wider and squatter you make the graph, the more flat, steady, and

stable the red line will appear. If you make the graph squat enough,

there is zero

increase of debt. This does not work with numbers, of course, but you

can probably create in readers' minds the impression you want to create, by making your

graph more wide and less tall.

Cecchetti's glaringly wide graph provides

airquotes-evidence for the assertion that the debt-to-GDP ratio was

"steady" from the early 1950s to the mid-1980s. But that doesn't make

the assertion true.

Hey, I'm not saying the slope of the line in

the 1950s is as steep as the slope after 1980 or the one after 2000. But

the red line is not as flat in the 1950s as it is from the

mid-1960s to the early 1980s. Around the 1950s it slopes up for a decade

and

more. Debt-to-GDP was rising. And if increasing debt implies

financialization, then there was financialization in the 1950s.

It's not just Palley's paper and Cecchetti's. It's everywhere you look. Some years back in Finance is Not the Economy, Dirk Bezemer & Michael Hudson wrote:

Growth

in credit to the real sector [the "non-financial" sector] paralleled growth in nominal U.S. GDP from

the 1950s to the mid-1980s — that is, until financialization became

pervasive.

It's the same story Palley tells: the same

non-financial sector debt; the same debt-to-GDP ratio; the same three

decades; and the same stability before 1980 and financialization after.

Bezemer and Hudson also quote Richard Werner (2005) and Godley and Zezza (2006) making similar observations.

Evidence

Graph

#3 below is another look at the same debt we saw on graph #1 above. But

just the debt this time, not debt-to-GDP. And this time I show the debt

on a log scale.

On a log scale graph, a straight line at any

angle is a constant rate of change. For any two straight lines, the

steeper one is increasing faster; the flatter one is increasing more

slowly.

On graph #3, the slope of the line -- the steepness of

it -- indicates how fast domestic non-financial debt is growing. The

steeper the line, the faster the growth of debt. The flatter the line,

the slower.

In the 1950s, the line goes up. In the 1960s the

slope is almost the same but it goes up a little faster than in the

1950s. In the 1970s the line definitely goes up faster than in the

1960s. So does the debt.

We didn't see increase in the 1960s and '70s on the first graph.

And yet, here it is:

|

Graph #3: The graph shows accelerating debt growth from

1951 to the mid-80s, and slowing debt growth since.

|

After the 1980 and 1982 recessions the line runs faster uphill for a few

years, but slows in the mid-80s and goes uphill at this slower pace until after the

year 2000. These are the years that debt is imagined to be growing very

fast according to Palley, according to Bezemer and Hudson, and according to Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli. All of them.

Don't

get me wrong. I think they are good economists. I love reading their

stuff, and I agree with most everything they say. But they have picked

up the idea that debt was "stable" before 1980, when in fact it was not.

And they build that error into their arguments and their theories,

creating an unsound foundation for their work. As a result they tell us

silly things, like financialization started in 1980.

This

is only a minor point. Or rather, it would be a minor point, if it

wasn't wrong. But it is wrong. And it is a most dangerous thing, to let

wrong ideas become embedded in economic thought.

Convince yourself

The level of non-financial debt accelerates upward through the 1950s, '60s, and '70s. It wiggles and writhes in the 1980s. By 1990, the acceleration of debt is a thing of the past, and the level of debt is rising only about as fast as it did in the 1950s. This is not the story economists tell. It is, however, the story the numbers tell.

Click

on graph #3 to see it bigger. Print it out, put a straightedge on it,

and see for yourself when debt growth was fast, when it was slow, and

when the changes occur. Eyeballing this stuff is better than taking

somebody's word for it. And, frankly, it is fun.

Again,

#3 shows just the debt, not debt-to-GDP. But the underlying perception

is that debt grew slowly before 1980, and fast after. And graph #3 is

the one that shows how fast debt is growing. Graph #1 doesn't show debt.

It shows a ratio.

Notice that graph #3 shows increase from 1951 to 2021. It is uphill all the way. Here is what I find with my straightedge:

- Domestic non-financial debt shows a straight run in the 1950s, then turns up a bit more just after the 1958 recession

- A straight run in the 1960s, with an upturn just after the 1970 recession.

- A short, straight run, slightly humped, and an upturn after the 1974 recession.

- A slightly humped run, and an upturn after the 1982 recession.

- This

is the fastest increase in debt so far, after the 1982 recession, but

it starts curving down almost immediately. Then there is a straight run

from 1990 to 2000 or say to about 2003. Then there is a small up-jog.

- The

straight run of the 1990s is less steep than that of the 1960s. It is

about the same as that of the 1950s but to my eye the 1990s increase is

slightly slower: Debt growth was slower in the 1990s than in the 1950s and '60s and '70s!

- Note

that when debt is fairly small (as in the 1950s) a significant increase

may pass unnoticed. But when debt is already uncomfortably large (as in

the 1990s) the same rate of increase seems massive because the numbers

are so big and debt is already problematic.

- Finally, the straight run between the 2009 recession and the covid year runs uphill at the slowest rate on the graph.

Don't

take my word for it. To convince yourself, do it yourself. It's

important, because everybody says debt was "stable" before 1980, but it

wasn't. Before 1980, debt was growing more rapidly with each new decade.

It slowed in the mid-80s, and after the 1980s debt increased at a slower rate.

Granted,

we're not looking at debt-to-GDP here. We're just looking at debt. But

the growth of debt was faster in the 1960s than in the '50s, and faster

in the 1970s than in the '60s. After that was there the rapid increase

of the 1980s, for a very short time. Debt growth slowed with the Savings

and Loan crisis, beginning in the mid-80s. And then, in the 1990s debt

growth was slower than debt growth in the 1950s and '60s.

The "debt was stable before 1980" story must be taken with a grain of salt.

The inflation complication

Who

tells the story that I tell? Nobody I know. When other people tell the story,

it is always non-financial debt relative to GDP. And no matter who tells

the story, the story is that debt growth was stable and steady,

relative to GDP, until the 1980s -- even though in the 1950s it was not -- and that after 1980 debt growth accelerated:

- Palley, p.31: "Prior to 1980, the domestic non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio was stable."

- Mason and Jayadev, p.2: "Between 1950 and 1980, the ratio of total nonfinancial debt to GDP was quite stable around 1.3 ..."

- Benjamin Friedman, 1981, p.1: "The aggregate outstanding indebtedness of

all nonfinancial borrowers in the United States has been approximately

$1.40 for each $1.00 of the economy's gross national product, ever since

World War II."

- Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli,

p.6: "As Graph 2 shows, the US non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio was

steady at around 150% from the early 1950s until the mid-1980s."

- Bezemer and Hudson:

"Growth in credit to the real sector paralleled growth in nominal U.S.

GDP from the 1950s to the mid-1980s — that is, until financialization

became pervasive."

But no matter who is telling the story, I never find them saying something like this: It might be that

debt grew slowly before the 1980s and fast after. But it might be that

GDP grew fast before the 1980s and slowly after.

But

GDP growth is not the topic of the moment. The topic is the

complication that GDP brings into the ratio: The inflation complication:

Inflation changes GDP much more than it changes debt. Inflation

increases the whole GDP number. But inflation increases only about one-tenth of the debt number, maybe less.

Here is the complication, in two bullet points. Bear with me:

- Inflation changes prices and values for the current year's transactions. It affects all of GDP because the current year's GDP counts the current year's "final" spending, but does not count the final spending of other years. (Last year's final spending was counted in last year's GDP and was inflated by last year's inflation.)

- Inflation

changes all of GDP, but it changes only a small part of debt. Inflation only

affects the current year's purchases on credit. Debt includes the credit purchases from previous years (unless they've been paid off) but inflation doesn't change them. Inflation doesn't change existing debt. (Additions to debt from

prior years were inflated when those years were current.)

Here is the important point: Inflation

affects all of GDP but only a small part of debt. Therefore, inflation

increases the debt number a lot less than it increases the GDP number.

This lowers the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Inflation reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Inflation reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio

The big inflation that I remember is the one called "the Great Inflation" of 1965-1984. If we never had those years of high inflation, the debt-to-GDP ratio for those years would not have been reduced, and graph #1 would have turned out more like this:

|

Graph #4: Inflation messes with the debt-to-GDP ratio

|

The debt-to-GDP ratio ran low in the 1960s and '70s because of the long period of severe inflation. Somebody laid an egg.

|

Graph #5: I want you to picture this whenever you see a graph like #1

|

Inflation

increases the GDP number more than it increases the debt number.

Therefore, inflation lowers the debt-to-GDP ratio. This is what we

see on Graph #5: not that "debt was stable" in those years, and not that

the growth of debt was low, but that the ratio was reduced by

inflation.

Can it be that economists are unaware of this? I doubt it. But somehow,

they can't even seem to find the increase of the 1950s on their

debt-to-GDP graphs. Maybe they should make their graphs taller and not so wide.

Why it looks like debt growth was low before 1980

Graph #3 shows debt rising in the 1950s, rising faster in the 1960s, and rising faster yet in the 1970s. Graph #1 tells a different story.

The increase of the 1950s can be seen in the debt-to-GDP ratio on graph #1, yes. But no comparable increase shows up on that graph in the 1960s and '70s. How can this be?

The

answer? Inflation. Inflation reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio. In the 1960s and '70s there was a "Great Inflation" that kept the debt-to-GDP ratio low, and made the

ratio look "stable" in the years before 1980.

Funny thing.

Everybody knows about the horrific inflation of the 1960s and '70s. But

those years of inflation never gets mentioned when people are

talking about how wonderfully low and stable debt was in those years.

1980 as a turning point

A

big part of Thomas Palley's attention in the PDF is directed to the

1980 start-date of financialization. For Bezemer and Hudson, it is the

mid-1980s and "pervasive" financialization. Cecchetti doesn't use the

term "financialization", but the data he studies begins in 1980.

Mason and Jayadev's paper is a study "in explaining rising debt levels,

especially between 1980 and 2000." And Benjamin Friedman followed up

on his 1981 paper in 1986, saying "The U.S. economy's nonfinancial debt ratio

has risen since 1980 to a level that is extraordinary in comparison with

prior historical experience."

Why is 1980 such an important turning point?

Back

before 1980, our growing debt wasn't very troubling because inflation

was driving income up. But then a wonderful thing happened: Paul Volcker

conquered inflation.

As a result, debt started growing faster

than income; faster than GDP. And on the debt-to-GDP

graph, you see debt shooting up because of Volcker's success.

The mirage

Thomas Palley attributes the sudden rapid growth of debt after

1980 to financialization. But there was no sudden rapid growth of debt after

1980. The sudden growth of debt is an illusion created by the ending of

the Great Inflation.