Inflation & the Rise of the Government Sector: An Analytical Survey (1979) by John H. Hotson

Hotson's opening:

That

the rise of the government sector in recent decades is the root cause

of the inflation which has plagued these same decades is not a thought

which has occurred forcefully to many economists.

Hotson's

observation, reinforced by the title of his article, offers support

for my running argument that cost-push inflation is driven by the growth of

finance:

- Each sector of the economy is a cost to the rest of the economy.

- The growth of one sector, relative to the rest of the economy, creates cost-push pressure.

- Unless the central bank relieves the cost pressure by allowing inflation, cost pressure slows economic growth.

- Sector

growth is liable to be a long-term phenomenon, so that the containment

of inflation is likely to create long-term slowing of the economy, as

the developed world has seen over the past 60 years.

Hotson reinforces his observation with a quote from Robert Heilbroner:

When

we look at the historical picture, the root cause of the recent

inflationary phenomenon suggests itself immediately. It is a change that

profoundly distinguishes modern capitalism from the capitalism of the

prewar era - the presence of a government sector vastly larger and far

more intimately enmeshed in the process of capitalist growth than can be

discovered anywhere prior to World War II ...

I would change two of Heilbroner's words to one:

... the presence of any sector vastly larger and far more

intimately enmeshed in the process of capitalist growth than can be

discovered anywhere prior to World War II ...

and that about sums it up.

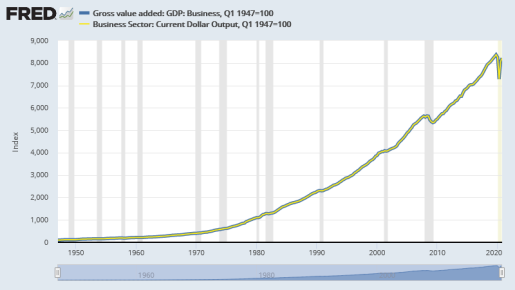

One

measure of size, commonly used as a measure of problems related to

government, is the size of the debt. Here's an old graph of total

debt, and five components of it, shown relative to GDP:

The

graph doesn't show where we are now. But it does show what happened

during the time the economy went from "good" to "bad". I'll paraphrase

what I said about it before:

The topmost plotted line shows total debt. On the

right-hand side of the graph, the next line down from the top is "Domestic Financial" debt.

On the right-hand side, the most recent numbers show domestic financial

debt is the largest component of the debt. On the left-hand side, the graph shows domestic financial debt was the smallest component in the 1960s.

Clearly, domestic financial debt has been the fastest-growing component of our debt.

The growth of one sector, relative to the rest of the economy, creates cost-push pressure.

If the sector's growth is natural, it may not be a problem. But

if the growth arises from an unnatural cause such as economic policy

that consistently favors the growth of finance, it could very easily be a

problem, and one most difficult to solve.

Let me paraphrase Hotson's Heilbroner quote:

The

graph shows the presence of a financial sector vastly larger and far

more

intimately enmeshed in the economy than can be

discovered anywhere prior to World War II ... When we look at this

historical picture, the root cause of the recent inflationary phenomenon

suggests itself immediately.

These days, inflation

is among the least of our economic problems. Forgive Hotson and

Heilbroner their focus on inflation. Hotson was writing in 1979,

Heilbroner in 1978.

Me, I have a somewhat different concern.

Do keep in mind two things. First, economists' diagrams of inflation show that

- Demand-pull inflation works itself out through faster economic growth

- Cost-push inflation works itself out through slower economic growth

Economist Frederic Mishkin explains:

[D]emand-pull

inflation will be associated with periods when output is above the

natural rate level, while cost-push inflation is associated with periods

when output is below the natural rate level.

The

growth of finance creates cost-push inflation, not demand-pull. So we

can simplify the Mishkin quote by omitting the "demand-pull" part:

Mishkin says "cost-push inflation is associated with periods when output

is below the natural rate level." Output "below the natural rate level"

means economic growth is slow. Mishkin is saying that cost-push

inflation makes the economy slow.

The economists' diagrams tell us the same thing: cost-push inflation makes the economy slow.

I prefer to think that cost pressure

makes the economy slow, and that if they let some inflation occur, the

central bank relieves some of that pressure and the economy slows less.

But we can go with it Mishkin's way for now, if you prefer.

Mishkin's

statement makes sense if we assume cost-push inflation is temporary: We

get a few years of slow growth, and then things return to normal.

Economic performance returns to the natural rate level.

But if the

inflation is sustained

But if the cost pressure is sustained, the economy will seem to be permanently below

the old natural rate level. Economists will say the natural rate has

fallen, and they will lower their estimate of the natural rate. At

least, that's what happens with potential output.

The new estimate may bring the natural rate down to the actual growth level. We can, however, expect the cost

pressure to continue driving actual economic growth down until it is

again below the estimated natural rate. But this doesn't happen

because "cost-push inflation is associated with periods when output is

below the natural rate level." It happens because cost pressure reduces

economic growth.

Maybe we should look at the natural rate as

a best-case estimate of growth, an estimate that arises from actual

economic performance. The economy doesn't grow slowly because the

natural rate is low. It's the other way around: The natural rate is low

because the economy is growing slowly.

Furthermore, if cost pressure has made the economy slow but the cost pressure still exists, the economy will slow more.

This

is what happens when the inflation is cost-push. It continues to happen

as long as the cost problem continues to exist, and it happens whether

the central bank allows inflation or not. Do what you will -- abandon

Keynesian theory, come up with supply-side policies to boost

economic growth, deregulate finance, whatever -- the decline of growth continues regardless, until the cost

problem is resolved, one way or another, for better or worse, rising

again or falling to ruin.

"And on the pedestal these words appear:

'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!'

Nothing beside remains..."

Scott Sumner said

I

am not denying that growth in US living standards slowed after 1973,

rather I am arguing that it would have slowed more had we not reformed

our economy.

Yes, the economy slowed. Yes, the

reforms helped. But the reforms did not solve the problem. They did not

solve the cost problem. And after Paul Volcker solved the inflation

problem in the early 1980s, economists quit looking for a cost problem.

Instead, they defined "cost-push" out of existence.

And

since the reforms did not address the underlying cause of slow growth

-- the cost problem created by the continuing growth of finance -- the

economy continued slowing despite being boosted by reforms. Things grew

worse, and here we are today, starry-eyed and hopeful that the

post-pandemic economy will grow enough to somehow justify the inflation

we are now being told to expect.

And that's how cost pressure works. Inflation is not the problem we must focus on.

The

second thing to keep in mind is the slowdown of economic growth. And

that the solution is to reduce the size of finance, the overgrown sector that is the

source of the cost pressure. We must also eliminate the policies

that induce excessive growth in that sector.