A record annual pace? Maybe I'm missing something here, but inflation

now is nowhere close to the double-digit inflation of the 1970s.

- Link to the article at Fox Business

- Image of the article at Fox Business

I'm not finding a date for the article, but in the HTML it says

<meta data-n-head="ssr" data-hid="dc.date" name="dc.date" content="2021-10-29">

so 29 October, the same day I'm making these notes. Okay, yeah, and the "Updated" field on the FRED Graph page says "7:43 AM CDT" -- the same day, or else there would be a date there.

Just checking.

The article's opening statement:

The core personal consumption expenditures index, the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure, continued to climb at the fastest annual pace on record in September.

The fastest annual pace on record? I don't think so.

Looking for info on "the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure", I come across this item from Fox Business dated August 27, 2021; presumably the July 2021 inflation:

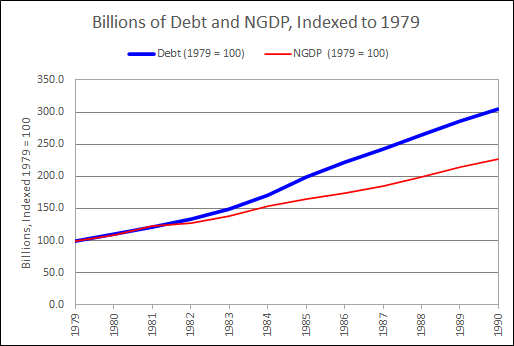

Inflation "soars by most in 30 years". That I can believe. I already looked at this graph, showing "Percent Change from Year Ago" inflation:

|

| Graph #1 (Click the graph to see it bigger) |

At the extreme right of the graph, inflation shoots up to 3.6 percent. Then if you look 30 years earlier, around 1990 (near the middle of the graph), there's a label pointing to March 1991 when inflation was 3.65 percent. Inflation now is the highest since then, but not a record.

I still don't know what they're talking about when

they say inflation is presently at "a record annual pace". What record?

If you look back a little farther in time on the graph you can see

inflation peaking in 1975 and again in 1981, both near 10% annual.

Looks to me like the January 1975 inflation rate is the record.

I

don't find anything telling me which one of FRED's 816,000 datasets is

"the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure". I'm on my own here.

The Fox Business article mentions the "core personal consumption

expenditures index". (That's the PCE index, not the CPI.)

They

also say "Core PCE ... excludes food and energy prices". (I think "core"

is a keyword the Fed uses to mean "excludes food and energy prices".)

I looked up core pce at FRED and went with the first one they turned up: Personal Consumption Expenditures Excluding Food and Energy (Chain-Type Price Index).

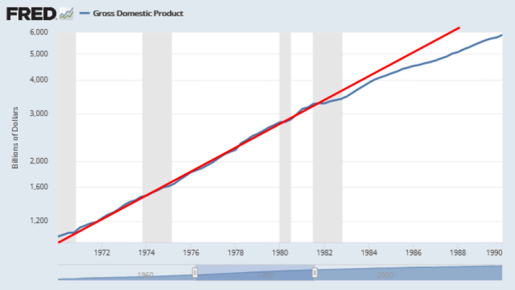

The numbers are right. On graph #2, in the upper-left of the graph area

an information box shows 3.5% inflation for May and 3.6% for June,

July, August, and September.

|

| Graph #2 (click to enlarge) |

The dots are months. The rightmost dot is September. Fox Business gives the same numbers FRED gives, 3.6% for the last four months:

Core PCE, which excludes food and energy prices, last month rose 3.6% year over year, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Core prices have accelerated by that amount for four straight months.

They omit May. But the other numbers match. We're looking at the same graph Fox Biz is looking at.

They

make the inflation sound pretty nasty, don't they? "Core prices have

accelerated by that amount for four straight months." The Sunday

morning talk shows that I mentioned on the 20th, in Inflation show-and-tell, also made the inflation sound pretty nasty.

I'm

not too concerned about the inflation we've been getting. I'm more

concerned about the inflation the media may be creating out of

ignorance. The inflation numbers we're looking at measure "percent

change from year ago".

Inflation didn't go up 3.6% between August and September. It went up

3.6% between September of 2020 and September of 2021. Inflation's not as bad as they make it sound.

This next graph shows both the from-year-ago change and the from-last-month change:

|

| Graph #3 (click to enlarge) |

The red line shows percent change from one month ago; the blue line shows percent change from 12 months ago. So you would expect the blue line to be higher, and sure enough it is.

It's hard to see without making the graph bigger, but the big increase in the blue line runs from the low in February 2021, to the high in April. After that it runs almost flat, with the 3.5% in May and then June thru September at 3.6%.

You can see a similar increase in the red change-from-one-month-ago line: There's a low in February 2021 and a high in April. After April, the month-to-month numbers actually go down. Since May, the price increases have been getting smaller. That's why I say I'm not too concerned about the inflation we've been getting.

As I said before, if you get one month of high inflation, that high number stays in the "percent change from year ago" calculation for a whole year. It makes inflation look persistent when it is not. That's why it's important to look at the red line, the month-to-month numbers.

|

| Graph #4 (click to enlarge) |

The red line on Graph #3 is shown in blue on #4. The from-year-ago graph is gone.

Graph #4 shows a lot more months than #3. Don't let that confuse you. What I want you to see is the low of April 2020 and the high of April 2021.

When they figured from-year-ago inflation for March 2021, the low of April 2020 was still in the calculation. But when they figured the from-year-ago for April 2021, the old data (April 2020) came out of the calculation. It was replaced by the monthly high of April 2021.

Replacing the low monthly number with a high one -- burning the candle

at both ends, so to speak -- made the from-year-ago inflation increase

look unusually big and threatening. That's why on Graph #3 the March-to-April 2021 increase is disproportionately bigger in the blue line than in the red. That's why the gap between red and blue opens up so much with the April number.

The April 2021

increase was big, but not as big as the from-year-ago number makes it

seem. It seems big because the unusual low came out of the calculation.

This kind of figuring is the reason Graph #3 shows the blue line

stubbornly high, even though the red line is already back down in the

normal range of inflation. And this kind of figuring will happen again next month and the month after.

About halfway between April 2020

and April 2021 on Graph #4, the blue line shows two months in a row at

the zero level. No inflation. Those two months are October and November

of 2020. The October 2021 from-year-ago inflation will have this month

of no inflation dropping out of the calculation. Any inflation will be high by comparison, making the from-year-ago number look big.

And then a month later, the zero inflation of November 2020 will come out of the November 2021 report. This mathematical chicanery will again make the from-year-ago inflation number seem worrisome.

There'll be

inflation, but it won't be as bad as the news will make it sound. To get a

feel for what's happening with prices, pay a lot of attention to the

month-to-month numbers, and not so much to the from-year-ago numbers.

One more graph to look at: index values. The index values are like the price level, as opposed to the "change-in" numbers we've been looking at.

On Graph #5 the line goes up just as prices go up.

|

| Graph #5 (click to enlarge) |

The flatter the line, the less the rise of prices. The steeper the line, the more the rise of prices.

On

this graph we can see prices going up more quickly after February 2021

than before. And after May 2021 we can see the line flattening and a

slowing of inflation. That's what you need to know. You can see it here, and you can see it in the red line on Graph #3.