|

| Graph #1: Median relative to Mean since 1953 |

"The commonwealth was not yet lost in Tiberius's days, but it was already doomed and Rome knew it. The fundamental trouble could not be cured. In Italy, labor could not support life..." - Vladimir Simkhovitch, "Rome's Fall Reconsidered"

Monday, March 29, 2021

Sunday, March 28, 2021

How come nobody says "THAT'S WHY GROWTH IS SLOWING!"

I'm still working on posts for my "Terms of the

Times" series. It's slow going. Everything about the economy is related

to everything else, and I'm trying to find a path through it all. I often go

off on a tangent. I'm starting to cut these tangents off and, rather

than deleting them all, posting some of them so you know I'm not dead

yet. Anyway, this is one of them.

It is starting to make sense to me, finally, this focus on cost-push inflation as "the decrease in the aggregate supply of goods and services stemming from an increase in the cost of production". It

is the most important difference between cost-push and demand-pull,

this phrase "decrease in aggregate supply" that they now use in

definitions of cost-push inflation.

Of course I've known for a while now that rising cost hinders growth:

The growth-side problem is rising cost. Rising cost inhibits growth. And it turns out that creating some inflation compensates for rising cost and gets us a little growth.

But I started out with an older definition of cost-push inflation, such as you can still find at policonomics:

Cost-push inflation occurs as a response of agents raising prices to maintain their profit margins if there are higher production costs.

The old explanation makes it clear that the problem is rising cost and falling profit. But it took me a while to figure out that cost problems hinder economic growth. I'm never quick, coming to realizations like that on my own. These days, they put it right there in the definition, as Investopedia does, the decrease in aggregate supply stemming from an increase in the cost of production.

Never quick. I know they're not making things up. I know that the decrease in aggregate supply -- the slowdown of economic growth -- results from the cost pressure. But my response to the revised definition, for the longest time, is: No.

Even now, when Investopedia defines cost-push inflation as "decrease in the aggregate supply" I want to say No. I want to say inflation is not supply. Inflation is prices. Inflation is prices going up, not supply going down. Yes, I know, price and supply are related. But no, inflation is not a change in supply.

God, there are still people who say inflation is an increase in the quantity of money. When I came to it, inflation was already an increase in prices, the general level of prices. People who grew up with the older view than mine object to thinking of inflation in terms of price, apparently because it severs the connection where increasing the money causes the increase in prices. Or maybe because bringing up the older definition seems (to those people) a strong argument that says the money inflation causes the price inflation.

And here I am, just like those guys, grumbling about a revised definition.

Here's

a question. If they do all the work for you now, so you don't have to

realize for yourself that cost-push inflation slows the economy, how

come nobody says "THAT'S WHY GROWTH IS SLOWING!" How come there are a

million explanations of slowing growth, and none of them identify cost

pressure as the problem?

This whole evolution of the old "cost-push" idea into the "supply side" inflation driven by "supply shocks", this has to have originated with supply-side economists. And apparently it was adopted by the descendants of the post-war Keynesians. Okay.

But how come these days they all say

cost-push makes the economy slow, and none of them say WOW THAT MUST BE

WHY OUR ECONOMY IS SLOW! or even MAYBE THAT'S WHY...

I dunno. Maybe the reason goes something like this?

- They define "inflation" as not just a jiggle in prices, but a "sustained" increase.

- They change the name from "cost-push" inflation to "supply side" inflation.

- They define supply side inflation as caused by "shocks".

- They observe that supply shocks are "temporary".

- They conclude that supply shocks do not cause inflation because inflation is "sustained".

- Far as I can tell, they never consider the possibility that cost-push might arise from something other than shocks. And

- They never consider the possibility that "sustained" cost-push could exist.

Hey, you can define cost-push inflation out of existence, if you want to. But that doesn't make cost pressure go away,

I

know some economists talk about "conflict" inflation and "built-in"

inflation and "inflation expectations". These are ways to take a

temporary inflation and turn it into sustained inflation. Not sure, but I

think these discussions come mostly from the descendants of the 1960s

Keynesians and from Marxists or "Marxians" (I sure do wish the names of

things didn't keep changing) -- and these are the economists that should be most willing

to accept the idea of sustained cost-push inflation.

Well, certainly, if a temporary supply shock leads to built-in inflation, then you've got sustained inflation. But the cause of this sustained inflation is not the same as the cause of the temporary inflation that started it. And I don't see that the sustained inflation that results is necessarily cost-push or supply-side inflation. I don't see that, at all.

I dunno. I've not looked into these things enough. But it seems to me that if you are concerned about the cost pressure that underlies cost-push inflation, you're wasting your time when you adopt a story that wanders away from the cost-pressure story just so you can explain "sustained" inflation.

To each his own, I suppose.

Saturday, March 27, 2021

Comparing Households & Nonfinancial Corporate Business: Interest Paid

|

| Graph #1: Interest paid by households, relative to interest paid by NCB |

Now that's a spike!

At the 1.0 level, the two measures of interest are equal. At 2.0, household interest paid is twice the level of interest paid by nonfinancial corporate business.

The starting value (in 1946) is 0.94191, or 94 percent. Household interest costs were almost as much as NCB interest costs.

At the peak in 1956 the value is 1.99490, or 199.5 percent: Household interest costs are twice the level of NCB interest costs.

It occurs to me that this initial spike is related to a spike in household borrowing and spending. Can't really tell from this graph. But that spike in spending would likely have had a lot to do with economic recovery and "golden age" following the second World War. At the time, a lot of economists were expecting secular stagnation. That didn't happen.

Again, this isn't the right graph to see it, but I'm also thinking that the 1946-1956 spike in interest cost was at least partly responsible for creating a rising cost of living, and perhaps for helping to create the inflation of 1955-1958 that Samuelson and Solow (1960) could not explain.

Two things to look into, for another day.

And another: How did interest costs manage to fall so fast, between 1965 and 1970? But again this is the wrong graph. Maybe what looks like a big drop in household interest cost was really a big increase in nonfinancial corporate business interest expense.

Another day.

Friday, March 26, 2021

By the time the insurrections start, the end is near

Real GDP relative to Potential GDP (quarterly data):

|

| Like the Second Graph from the 25th, but in Excel and with a Hodrick-Prescott Added |

The differences between Real and Potential GDP are small: Generally 4% of Potential or less. Thus the blue line is mostly between 0.96 and 1.04. But this ignores the obvious downtrend which tells us things are getting worse.

Before the mid-1970s the blue line spent a lot of

time above the 1.02 level and very little time below the 0.98 level.

Thus in the early years the trend lines are high.

Since the mid-1970s, blue has spent very little time above 1.02. And the time spent below 0.98 is longer -- the "V"-shaped lows are wider at the 0.98 level than they are in the early years -- and the lows are frequently lower than in the early years. Thus in the middle and later years, the trend lines are lower.

Since I had the spreadsheet open, I started counting "good" and "bad" economic performance. I used the same measure I used above: two percent or more above Potential is "good" performance; two percent or more below Potential is "bad".

The counts of mid-range performance (within ±2% of Potential) were high in all three time periods, ranging from 48 to 70. It's the data to the left and right on the graph, the low performance and high performance data counts, that really shows what happened.

Looking

at "high" performance, on the right, it turns out that 1949-1973

has almost as many quarters of high performance as it has "mid-range" performance.

The 1974-1994 period had one single quarter of high performance. The

1995-2019 period had two, and that's it.

The rest of the data is on the left, shown by the "low" performance bars. High numbers for 1974-1994 and 1995-2019, both. A low number for the early years, 1949-1973.

Don't be deceived

by the mid-range bars. All three time periods have high counts of

mid-range performance. But look what happened with the high and low performance data:

For the 1949-1973 period it was mostly high performance. For the other

periods, almost everything was low performance. Mid-range and high for 1949-1973; mid-range and low after 1973. That's the difference.

In The Causes of Inflation Frederic S. Mishkin wrote:

Mishkin says it would be easy to tell whether inflation was cost-push or demand-pull if we could trust the numbers we have for Potential GDP. But we can't trust that data, he says. Maybe so, but that doesn't stop the Fed from relying on Potential GDP when they use the Taylor rule or when they make policy decisions based on the Phillips curve and stuff like that.... demand-pull inflation will be associated with periods when output is above the natural rate level, while cost-push inflation is associated with periods when output is below the natural rate level. It would then be quite easy to distinguish which type of inflation is occurring-if we knew what the value of the natural rate of unemployment or output is. Unfortunately, the economics profession has not been able to ascertain the value of the natural rate of unemployment or output with a high degree of confidence.

Real GDP is in decline relative to Potential GDP, and it looks like the decline has been persistent and deepening since 1949. That doesn't look random to me. Nor does it look like a whole series of estimation errors. I think Potential GDP data is fairly trustworthy. And I think Real GDP persistently below Potential is telling us something we'd rather not know.

Real GDP is in long-term decline relative to Potential GDP. On top of that, if you go back to the first graph in yesterday's post, Potential GDP is also in long-term decline. So GDP is declining relative to something that is in decline, and this "something" just happens to be our best estimate of best-case GDP.

Conclusion: GDP is in a troubling decline. Gradual, yes,

but troubling. And GDP is largely below Potential, meaning we should expect inflation to be cost-push inflation. So we have a cost pressure problem that contributes to further decline.

Now let me remind you what I've been writing

about lately in my "Terms of the Times" series: cost pressure, which is

usually called cost-push inflation because of the effect it has on the

price level. But I've also been saying that the problem with cost pressure

is not so much the inflation as it is economic decline. Cost pressure

creates economic decline. You saw the graphs, right? Something is driving GDP growth down.

Mishkin says cost-push inflation is associated with periods

when Real GDP is below Potential. The trend lines say Real GDP has been below Potential since the mid-70s. Mishkin might not want to bet on it, but maybe all the inflation we had for the last 45 years was cost-push inflation and it has been slowing the economy for 45 years. This is the warning that emerges from Mishkin's observation.

As I would say it, cost pressure creates economic decline unless the pressure is fully relieved by inflation, probably on purpose, by policy. As economists and their diagrams say it, cost pressure creates economic decline anyway, whether or not the pressure is relieved by inflation.

The only people who don't say cost pressure creates

economic decline are the people who get fired-up when they hear the syllables

"cost-push" and immediately get loud and vocal on the problem of inflation. But

that doesn't mean there's no economic decline. It means they overlook the decline that cost-push creates because they got fired-up before they thought the problem through to the end. And, unfortunately, the harder you fight

inflation the greater the economic decline you get from the cost pressure, because the pressure isn't getting relieved by inflation.

I'll say this one more time and then I'm gonna go take a nap. If cost pressure exists, GDP growth is in decline for sure. And if you restrain the inflation at all, and maybe even if you don't, the decline deepens.

The solution, however, is *NOT* to accept inflation as the "least worst" option.

The

solution is to figure out the source of the cost pressure -- HINT: the

excessive cost of excessive finance -- and reduce that cost.

Now you might think, as I think, that the Federal Reserve tried to

reduce the cost of finance in 2008 by reducing interest rates

to absolute zero. But the low rates only had immediate impact on *NEW*

borrowing, and there was plenty of old, existing debt, plenty of it, enough that

finance was still excessively costly. And it still is.

The Fed still hasn't done anything to relieve that problem. Nor has Congress. So the cost pressure remains. Economic decline continues. And we still have inflation.

Thursday, March 25, 2021

GDP: Going downhill, even relative to going downhill

Two graphs from Terms of the Times (2c)

If you take Real Potential GDP from FRED, show it as "percent change from year ago", cut it off at 2019 to eliminate the covid year and the prediction out to 2031, bring it into Excel, and put a linear trend line on it, this is what you get:

US Potential GDP Growth Rate:

|

| Source: FRED data, Excel Graph & Trend |

You say to yourself: Potential GDP growth -- best case

GPD growth -- sure is going downhill. The trend line shows a drop from

something over 4% annual growth in 1950, to something over 2% now. And

the trend line is based on data that ends in 2007, to eliminate the

downer effects of the "Great Recession" and all that came after it.

Then you start to wonder how GDP compares to this "best case" scenario.

I went back to FRED, got Real GDP and Real Potential GDP, both in billions, and made a graph of the ratio, Real GDP relative to Potential. Brought this data into Excel and duplicated the graph. I added a linear trend line (based on data thru 2019 this time), made both the plotted line and the trend line red, and erased the background and the axes to make a useful overlay.

I brought the FRED graph into Excel, put

the overlay on top of it, and stretched and moved the overlay until my

red plotted line lined up with FRED's plotted line. I love doing stuff

like that when I should be working. Anyway, here is the result:

US Real GDP relative to Potential:

|

| Source: FRED with Excel overlay in red |

My

red plotted line matches FRED's blue plotted line, within a pixel or

so. That's how I know I have the trend line in the right place.

Notice that my plotted red line stops at the high point on the right, just before the covid-inspired collapse that FRED's line shows. My trend line is not influenced by the covid collapse.

The trend line is above

1.00 (Real GDP more than Potential) in 1950, and below 1.00 (Real GDP

less than potential) in 2019. Real GDP used to be above potential, and

now it is below. And remember what the first graph shows: In 1950,

potential GDP growth was great, and now it sucks.

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

Terms of the Times (3a): Before the Great Inflation

The Great Inflation from 1965 to 1984 is the climactic monetary event of the last part of the 20th century.

Truman

1952 steel strike:

The 1952 steel strike was a strike by the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) against U.S. Steel (USS) and nine other steelmakers. The strike was scheduled to begin on April 9, 1952, but US President Harry Truman nationalized the American steel industry hours before the workers walked out. The steel companies sued to regain control of their facilities. On June 2, 1952, in a landmark decision, the US Supreme Court ruled in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952), that the President lacked the authority to seize the steel mills.

The Steelworkers struck to win a wage increase. The strike lasted 53 days and ended on July 24, 1952 on essentially the same terms that the union had proposed four months earlier.

Eisenhower

The presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower began at noon EST on January 20, 1953, with his inauguration as the 34th president of the United States, and ended on January 20, 1961...

There were three recessions during Eisenhower's administration—July 1953 through May 1954, August 1957 through April 1958, and April 1960 through February 1961, caused by the Federal Reserve clamping down too tight on the money supply in an effort to wring out lingering wartime inflation.

Three brief notes on inflation, from The Eisenhower Encyclopedia,

Ike saw Senator Taft give a speech in the late 1940s asking Americans to eat less to lower food prices. Liberals criticized the speech, but Ike agreed with Taft “one-hundred percent.”

Ike sawed off pieces of wood at rallies during the 1952 election to show the effect inflation had on money. (Baier, Three Days in January)

Ike ended the Korean War in July 1953. The war’s end caused the government to decrease its armament purchases. Unemployment rose from 2.6% to 6.1% by September 1954. Arthur Burns, an economic advisor, said Ike should cut taxes and expand public works programs to reverse the economic downturn. Secretary Humphrey objected. Ike sided with Burns and pushed for a $7 billion tax cut. He also signed legislation extending unemployment benefits for four million workers. This deficit spending ended the small recession in less than a year. (Gellman, The President and the Apprentice)

and two on steel:

Ike criticized Truman’s seizure of the steel mills during the 1952 Steel strike. (Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier and President)

Ike initially wanted to stay out of the 1959 Steel Strike, saying, “These people must solve their own problems.” He finally evoked the Taft-Hartley Act to force the workers to return to their jobs. (Gellman, The President and the Apprentice)

Steel strike of 1959:

The steel strike of 1959 was a 116-day labor union strike (July 15 – November 7, 1959) by members of the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) that idled the steel industry throughout the United States. The strike occurred over management's demand that the union give up a contract clause which limited management's ability to change the number of workers assigned to a task or to introduce new work rules or machinery which would result in reduced hours or numbers of employees. The strike's effects persuaded President Dwight D. Eisenhower to invoke the back-to-work provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act. The union sued to have the Act declared unconstitutional, but the Supreme Court upheld the law.

The union eventually retained the contract clause and won minimal wage increases.

Kennedy

Background from The Los Angeles Times:

Kennedy used a tactic his economic advisor, Walter W. Heller, called “jawboning” to urge business and labor to behave responsibly. In Kennedy’s time, that meant pay increases shouldn’t exceed productivity gains--and price hikes shouldn’t exceed increases in wages.

As Heller explained, “jawboning” used “the power of public opinion and presidential persuasion"--the bully pulpit--and Kennedy did it with words and deeds.

In his [January 11] 1962 State of the Union, Kennedy declared, “Our first line of defense against inflation is the good sense and public spirit of business and labor--keeping their total increase in wages and profits in line with productivity. There is no statistical test to guide each company and each union. But I strongly urge them--for their country’s interest and their own--to apply the test of the public interest to these transactions.”

Soon, Kennedy’s call was questioned. U.S. Steel Corp. substantially increased its prices ...

Introduction :

Kennedy, since the Inaugural Address and beyond, had been asking Americans and American business to exercise restraint to enable the United States to meet it's obligations and strengthen it's economy. The Steel Workers of America agreed to hold off their demands for higher wages if the Steel Companies, on their part, would not raise the price of steel. The workers kept their end of the bargain, the companies did not, ordering a price increase after a strike was averted. This dishonest and irresponsible act angered Kennedy, as is made clear in the [ April 11 ] speech.

Background from People's World:

The Democrat, after just a year in office, was concerned about potentially rising inflation. His administration set an informal but well-publicized target of having wage increases and price hikes match productivity increases. Meanwhile, Steelworkers’ bargaining over a contract with the nation’s steel companies was getting nowhere.

The administration intervened. It didn’t want a rerun of the 4-month steel strike of 1959 under GOP President Eisenhower. Labor Secretary Arthur Goldberg, a longtime union counsel, mediated the talks. The two sides reached agreement on March 31.

The pact, with ten of the nation’s 11 steel companies, called for an increase in fringe benefits worth 10 cents an hour in 1962, but no wage hikes that year. Then-AFL-CIO President George Meany said that in the pact, the union “settled on a wage increase figure somewhat less than the Steelworkers thought they would get.”

Kennedy praised the contract as “obviously non-inflationary” and said both the USW and the steel firms showed “industrial statesmanship of the highest order.” The agreement also implicitly said the companies would not raise prices, as that would be inflationary.

But on April 10, Roger Blough, CEO of U.S. Steel, the largest of the firms, with 25% of the market, met Kennedy in the Oval Office and told him the company was immediately raising prices by $6 a ton – and that other steel companies would follow. Six did. The 3.5% hike enraged the president. What he said in public was biting – but he was even more caustic in private.

In an April 11, 1962 press conference, Kennedy called the price hikes “a wholly unjustifiable and irresponsible defiance of the public interest.” He criticized “a tiny handful of steel executives whose pursuit of power and profit exceeds their sense of public responsibility.” The execs had “utter contempt” for the U.S., Kennedy said. ...

News Conference 30, April 11, 1962:

THE PRESIDENT: Good afternoon. I have several announcements to make.

Simultaneous and identical actions of United States Steel and other leading steel corporations, increasing steel prices by some 6 dollars a ton, constitute a wholly unjustifiable and irresponsible defiance of the public interest...

The facts of the matter are that there is no justification for an increase in the steel prices. The recent settlement between the industry and the union, which does not even take place until July 1st, was widely acknowledged to be non-inflationary, and the whole purpose and effect of this Administration's role, which both parties understood, was to achieve an agreement which would make unnecessary any increase in prices.

Steel output per man is rising so fast that labor costs per ton of steel can actually be expected to decline in the next twelve months. And in fact, the Acting Commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics informed me this morning that, and I quote: "Employment costs per unit of steel output in 1961 were essentially the same as they were in 1958. " ...

Some time ago I asked each American to consider what he would do for his country and I asked the steel companies. In the last 24 hours we had their answer.

//

Seems to me there was a lot of

concern about inflation in those early years, before the period called

"the Great Inflation." Much of that concern was focused on cost-push. In Part 1

of this series we saw the great focus on "cost-push" between the early

1950s and the early 1970s, and since the early 1970s its decline, with

the rise of focus on "supply shocks". In Part 2 we observed the

evolution of terminology, in new concepts and changing definitions

arising with this change in focus.

In Part 3 we have already looked at the situation before the persistent and repeated rise of inflation that began in the mid-1960s. My further plan is to look into the differences between cost-push and demand-pull inflation, and the changes in economic thought on the subject -- in particular, the focus of economic thought on "temporary" versus "sustained" cost-push.

And I want to explore the once and future concept of sustained cost-push inflation.

Saturday, March 20, 2021

Terms of the Times (2c): Long-term economic decline

The whole long-term problem of declining economic growth could be due to cost pressure that we overlook because we took the "cost-push" concept and flushed it down the toilet.

US Real GDP Growth Rate:

|

| Source: Peterson Foundation |

US Real GDP per Capita:

|

| Source: Gallup |

US Real GDP Growth Rate (outside of recessions)

|

| Source: Forbes (Raul Elizalde) |

US Real GDP Growth Rate:

|

| Source: My graph. Elizalde's Method |

US Potential GDP Growth Rate:

|

| Source: FRED data, Excel Graph & Trend |

US Real GDP relative to Potential:

|

| Source: FRED with Excel overlay in red |

Fewer New Businesses:

|

| Source: FiveThirtyEight |

Less Expansion of New Businesses:

|

| Source: FiveThirtyEight |

Total Factor Productivity:

|

| Source: Robert Gordon |

Gross Fixed Investment:

|

| Source: Minneapolis Fed |

World and OECD Real GDP Growth Rates:

|

| Source: Lumen Learning |

G7 Real GDP Growth Rate:

|

| Source: Gavyn Davies blog at FT |

Eurozone Growth:

|

| Source: Economics Help |

Thursday, March 18, 2021

Terms of the Times (2b): A self-inflicted blindness

They assert without evidence that continuing cost pressure cannot exist; they beckon the decline of prosperity.

- Arthurian

Before

the Volcker Fed, economists searched for the cost that was the source of

cost-push inflation. That search was abandoned, unresolved, when Paul

Volcker worked his magic. Marcus Nunes gives away the magician's secret:

On becoming chairman of the Fed, Volker challenged the Keynesian orthodoxy which held that the high unemployment high inflation combination of the 1970´s demonstrated that inflation arose from cost-push and supply shocks ...

To Volker, the policy adopted by the FOMC “rests on a simple premise, documented by centuries of experience, that the inflation process is ultimately related to excessive growth in money and credit”.

This view, an overhaul of Fed doctrine, implicitly accepts that rising inflation is caused by “demand-pull” or excess aggregate demand or nominal spending.

Or, as Robert Hetzel said,

The central bank is the cause of inflation.

Or, as Mike Shedlock said, quoting a friend:

There actually is no such thing as 'cost push inflation'. Think about it - if the money supply were to remain stable (which isn't the case, but hypothetically), then a rise in price of some goods automatically would lead to a fall in prices of some other goods...

Economy-wide, a rise in general prices is only possible if the money supply increases.

Or, as Caroline Baum said:

This is one of those myths that never dies: cost-push inflation. Milton Friedman was adamant that both prices and costs rise in response to an increase in aggregate demand, which is a function of the Fed’s money creation.

Or, as Dallas S. Batten wrote in 1981, while Volcker was performing his magic:

The ultimate source of inflation is persistent excessive growth in aggregate demand resulting from persistent excessive growth in the supply of money.

Since

Volcker's time, the search for underlying cost pressure has been cast

aside, forgotten. Why bother to look for cost pressure? If the Fed can

control inflation by controlling the money, who cares about underlying

cost pressure? Who even cares?

I care, because cost pressure slows the economy.

Of course the monetary restriction we use to fight inflation slows the economy. This is Basil Fawlty's "bleeding obvious." But whether or not "the Fed can control inflation by controlling the money," it remains true that cost pressure not relieved by inflation finds relief by slowing the economy. It is obvious to me that if an increase in cost drives my profits down (and if profits were running low anyway because times are tough) then I'm going to have to raise my prices. The cost pressure forces my hand.

And if policy prevents the increase in my prices, then maybe my business fails: The economy gets a little slower, because of cost not relieved by inflation.

Note

that "wage and price controls" could have the same effect as "tight

money" in this regard, driving business out of business and slowing the

economy.

Note also that if profits have been running low

because times are tough, then cost pressure was probably reducing

profits and slowing the economy already for some years before rising

cost forced the closure of my (hypothetical) business.

Monetary restriction slows the economy. So does cost pressure that is not relieved by inflation. But here is something else, something I have trouble understanding: Cost pressure slows the economy even if inflation fully relieves the pressure. I can't make sense of it. But here it is, in the inflation diagrams:

|

| This

is a screen capture of slide 36 from a SlideShare presentation by

videoaakash15. You can click the image to visit the presentation. |

Note the direction of the arrows below the horizontal axis. As the diagrams show,

Under demand-pull inflation, output and income tend to grow faster. Under cost-push inflation, they tend to grow slower.

The cost-push diagram does not show Aggregate Supply shifting to the left as an alternative to a price increase. It shows prices rising and Aggregate Supply shifting left. The diagram indicates that both of these changes happen.

Like me, not everyone gets this. But I am starting to find people who do.

Frederic S. Mishkin, in The Causes of Inflation:

... demand-pull inflation will be associated with periods when output is above the natural rate level, while cost-push inflation is associated with periods when output is below the natural rate level.

Demand-pull goes with rapid growth, Mishkin says, and cost-push goes with slow growth.

Siddha Raj Bhatta, the Deputy Director at the Central Bank of Nepal:

In a less than fully employed economy, demand side inflation raises price level but at the same time output as well as employment level also rises. On the other hand, in supply side inflation, price level rises but employment and output falls due to decrease in supply. Thus, supply side inflation has two costs: fall in purchasing power and rise in unemployment.

The Deputy Director says demand-side

inflation helps grow jobs and the economy, while supply-side inflation

is harmful to growth and employment.

According to Tejvan Pettinger at Economics Help, cost-push inflation causes

- "a shift to the left of short run aggregate supply."

- "rising prices and falling real GDP."

- "a fall in living standards."

- "a fall in real wages."

If I was the cleaner for the ECB, Pettinger says, I’d be tempted to barge into a meeting and say

“It’s not the inflation you need to sort out, its the falling GDP!”

Taken out of context, of course, that last part.

What happens if cost pressure is not relieved?

Let me say again that I do not understand how cost-push slows the economy if the cost pressure is fully relieved by inflation. On the other hand, it is easy to see that a policy of restraining inflation will leave the cost pressure less than fully relieved, and will result in some slowing of economic growth.

Restraint of inflation is standard practice,

so my assumption is that cost pressure is always less than fully

relieved, and therefore that cost-push inflation does always cause

economic growth to slow.

Unfortunately, inflation is the lesser problem. Cost pressure is the greater problem.

It

seems that no

one who makes the "accommodation" argument -- no one who agrees with

Hetzel, Shedlock, Baum, Batten, and Volcker, for example -- stops to

wonder what happens

when cost pressure is not relieved by inflation. By failing to

accommodate the cost pressure, the monetary authority prevents

inflation, and that's as far as the thinking goes. But this policy

encourages the slowing of economic growth.

Imagine a case where mild, long-term cost pressure exists. It is mild, so neither the inflation nor the slowing of growth is troubling. But the Consumer Price Index rises from 102.1 in January 1984 to 262.231 after 37 years. Is that mild inflation, or are we just accustomed to it?

If any of that inflation was cost-push inflation, then economic growth was slowed by the cost pressure. If it continues for 37 years, the cumulative impact on growth must surely be troubling.

People say cost-push inflation is rare. That's wishful thinking.

People

have many explanations for the slowing of economic growth. All of these

probably have some merit. But no one seems to consider that a mild,

long-term cost pressure could be the driving force behind the gradual,

long-term decline of economic growth. It just doesn't fit with evolved thought.

The proper solution to cost-push inflation

The proper solution to cost-push inflation is not to raise interest rates and slow the economy further. The proper solution is to discover and eliminate the source of the cost pressure.

According to fully-evolved inflation theory, there's no such thing as cost-push. There is demand-pull demand side inflation, and there are "supply shocks". According to this theory, no solution is required because there cannot be a cost-push problem. That's like saying There is no God.

We cannot know. We can only assume. That's okay for religion, but not for economics.

My idea of the proper solution to cost-push inflation is, first, to admit that it might exist.

Keep your "simple premise, documented by centuries of experience, that the inflation process is ultimately related to excessive growth in money and credit". And keep the view that without monetary accommodation, there can be no inflation. I do. I maintain that view.

But consider the possibility that, should cost pressure arise, it would slow economic growth. As the inflation diagram shows, it might slow economic growth even if the Fed creates enough inflation to fully accommodate the cost pressure. It would certainly slow economic growth in any other case.

What is the proper solution to cost pressure and cost-push inflation? The proper solution is to discover and eliminate the source of cost pressure.

The Temporary Nature of Supply Shocks

Peter Cooper lays this out in a recent post at heteconomist:

A supply shock can cause one-off price hikes, independently of demand conditions, but for the one-off effect to act as a catalyst for cost-push inflation there needs to be a socioeconomic process capable of reinforcing the initial effect ...

Inflation is defined as a sustained

increase in the level of prices. You don't get a sustained increase

from a supply shock, because supply shocks by definition are "one-off"

events, as Cooper says. Or

- "one-time" events, as Robert Hetzel says. And Allan H. Meltzer. Or

- "temporary" as Tejvan Pettinger says. And Randal K. Quarles. And Milton Friedman, as paraphrased by Johannes A. Schwarzer.

Supply shocks don't create inflation, because supply shocks are temporary and inflation is sustained. That's the "evolved" view.

Five Key Points

You see where we end up:

- We have defined "inflation" as a sustained increase in the price level.

- We have replaced the term "cost-push" with "supply side" and we attribute supply side inflation to "supply shocks" and to nothing else.

- We have defined "shocks" as temporary, one-time, one-off events that are incapable of creating sustained inflation and therefore, by definition, incapable of creating inflation.

- We

end up with demand-pull (or demand-side) inflation -- the "too much

money chasing too few goods" inflation -- and supply-side (formerly

cost-push) inflation, which is by definition temporary (and therefore

not even inflation, by definition), and not something for the Federal

Reserve to muck around with. And

- We end up exactly as Scott Sumner said:

"There's supply side inflation, which is created by shocks like sudden increases in oil prices, and then demand side inflation caused by overspending in the economy. It's really demand side inflation that the Fed is concerned about. There's not much they can do about supply side inflation."

Sumner's view is the dominant, fully evolved view, far as I can tell. Supply-side non-flation is caused only

by economic "shocks". Therefore, there is no such thing as "cost

pressure" and, in particular, no such thing as "sustained cost

pressure."

I said earlier that I cannot lay out the chronology precisely. I am conscious of this as a weak point in this essay, and in my economics in general. So let me take a moment to strengthen the story a bit.

Frederic S. Mishkin's The Causes of Inflation is from September 1984. Mishkin wrote:

The conclusion reached in this paper is that in the last ten years there has been a convergence of views in the economics profession on the causes of inflation. As long as inflation is appropriately defined to be a sustained inflation, macroeconomic analysis, whether of the monetarist or Keynesian persuasion, leads to agreement with Milton Friedman's famous dictum, "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

To my ear Mishkin is saying that inflation was "appropriately" redefined some time between 1973 or '74 and 1983 or '84. Essentially, he is saying that inflation was redefined to work with other redefined or replaced terminology, in order to be able to reach a consensus that inflation is always demand-pull, always "a monetary phenomenon".

This validated the work of Paul Volcker (which, good grief, was still ongoing in 1984). The redefined terms validated the "simple premise, documented by centuries of experience, that the inflation process is ultimately related to excessive growth in money and credit". At the same time, the changes invalidated the concept of cost-push inflation, cost pressure as an economic phenomenon, and three decades or more of work on cost-push inflation.

If you define "supply shocks" as temporary, and "cost-push" as a temporary phenomenon induced by supply shocks, you are closing the door on the possibility of long-term consequences arising from continuing cost pressure. You are asserting, without evidence, that there is no such thing as long-term cost pressure.

In the process, you deny the possibility that an initially small cost problem could be responsible for the onset of a long-term economic decline. Your denial does not prevent this decline. But it will surely prevent you from understanding it.

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

Terms of the Times (2a): The evolution of cost-push

The whole concept of cost-push inflation has been pretty well extinguished from modern thought.

I cannot lay out the chronology precisely. But the concepts of inflation changed from demand-pull and cost-push, to demand-side and supply-side. Conceptually, this change was an improvement, as it finds supply and demand in inflation, just as econ theory finds supply and demand everywhere else in the economy.

But being conceptually better does not necessarily mean that the explanation of the cause of inflation is better, or that the statement of what must be done to stop the inflation is better. There is always an element of reality that may not follow from the elegance of theory.

The

terminology itself appears to have evolved, from cost-push inflation,

to cost-push created by supply shocks, to supply shock inflation, to

supply side inflation driven by shocks. In the highly evolved view of Scott Sumner,

There's supply side inflation, which is created by shocks like sudden increases in oil prices, and then demand side inflation caused by overspending in the economy. It's really demand side inflation that the Fed is concerned about. There's not much they can do about supply side inflation.

Sumner handles both sides of inflation in a single sentence, and two short sentences later he has said all he wants to say about inflation policy, without even using the words cost or push, in one very tidy package.

Then we have Jason Welker defining Cost-push inflation:

An increase in the average price level resulting from a decrease in aggregate supply.

A single sentence, brief, rich in meaning and clear as can be. But it seems somehow less evolved than Sumner's view: Welker certainly sees cost-push as supply-side inflation, and attributes it to a drop in supply, but he still refers to it as "cost-push".

Dunno. Clearly he has not yet abandoned the term cost-push.

But the link turned up in my "cost-push" search, and it is only a glossary

term. Welker's thinking could be nearly as evolved as Sumner's. Mine, happily, is not.

Here is Mike Moffat in Cost-Push Inflation vs. Demand-Pull Inflation, quoting from the textbook by Parkin and Bade:

"Inflation can result from a decrease in aggregate supply. The two main sources of a decrease in aggregate supply are:

- An increase in wage rates

- An increase in the prices of raw materials

These sources of a decrease in aggregate supply operate by increasing costs, and the resulting inflation is called cost-push inflation"

Parkin

and Bade have an increase in wages or prices creating a decrease in

aggregate supply that results in inflation. It is as if they feel

obligated to make cost-push a supply-side phenomenon, and they satisfy

this need by inserting the words "a decrease in aggregate supply"

between the increase in wages (or prices) and the resulting inflation.

This is nowhere near as tidy as Sumner's statement.

The Parkin

and Bade bit strikes me as clearly less evolved thought on the nature of

cost-push inflation. They have to force-fit "supply" into their

explanation.

From Arthur Burns and Inflation (PDF, 1998) by Robert L. Hetzel:

In November 1970, the minutes of the Board of Governors show Burns telling the Board (Board Minutes, 11/6/70, pp. 3115–17) that

prospects were dim for any easing of the cost-push inflation generated by union demands.

Union wage demands, leading to cost-push inflation. Again, Hetzel on Arthur Burns:

He believed that a central bank could cause inflation by monetizing government deficits but did not attribute inflation to that source in the early 1970s. Instead, he attributed it to the exercise of monopoly power by unions and large corporations...

Accordingly, President Nixon imposed wage and price controls August 15, 1971... Nevertheless, inflation rose to double digits by the end of 1973. So Burns attributed inflation to special factors, such as increases in food prices due to poor harvests and in oil prices due to the restriction of oil production...

"Special factors". Hetzel adds:

For Burns, the source of inflation changed regularly.

For Burns, the source of inflation changed regularly. Today's economists often rely on the idea of a series of unrelated, temporary shocks when they explain inflation. It's okay to do it now, I guess. But Hetzel strongly objects to Burns doing it:

Economists use models to learn about the world and to explain how it works. A model imposes a discipline by forcing the economist to explain cause and effect relationships within a framework that yields testable implications. When experience falsifies those implications, the economist must return to the model and examine its failures. The economist cannot “explain” the model’s failure to predict by assuming that the world’s underlying economic structure changes in an ongoing, unpredictable way. The evidence from Burns’s own words shows that he did not use such a model to predict inflation and, consequently, failed to learn from the inflationary experience of the 1960s and 1970s.

...

For Burns, the source of inflation changed regularly. He believed this view only reflected the complexity of a changing world. As a consequence, he did not have a model of inflation that could be contradicted by experience.

A pretty severe scolding, that.

There's not a lot of meat in Hetzel's view, but at least there is a lot of detail. Still, his analysis has as much the feel of gossip as of economics. This sense is confirmed by the denials that accompany Hetzel's evaluation of Burns:

To blame the inflation of the 1970s on an individual or on a group of individuals is too facile... Attributing policy failures to personal failures is a mistake that keeps one from learning. In this respect, it is helpful to view the high inflation of the 1970s as part of a learning process.

But not only gossip. We do find "special factors" offered as the cause of inflation, as long ago as the mid-1970s. But then, as Hetzel observes, "special factors are by nature one-time events. In 1974, inflation should have fallen as the effect of these one-time events dissipated..."

So we have the concept of the supply shock, if not the exact terminology, in the 1970s. We also have the temporary nature of supply shocks, though this insight may have been imposed on the 1970s by Hetzel, who was writing a generation later.

It looks to me as if Arthur Burns, Fed Chairman, presents a highly developed (but not evolved) version of cost-push. He knows cost-push is supply-side inflation, but does not seem to feel the need to focus on that aspect of it. He knows about special factors, though he does not call them "shocks". And in his day job, he searches for the cost-push pressure that is the source of the inflation.

Hetzel presents this search as fruitless and pointless. But then, Hetzel's economic thinking is more evolved than that of Burns. Hetzel has seen, and Burns has not, the implementation of stringent monetarism under Paul Volcker. The conclusion of Hetzel's paper makes this revolutionary evolutionary step perfectly clear:

The fundamental divide in monetary economics is whether the price level is a monetary or a nonmonetary phenomenon. If the price level is a monetary phenomenon, it varies to endow the nominal quantity of money with the real purchasing power desired by the public. The central bank is the cause of inflation.

...

Burns conducted monetary policy on the assumption that the price level is a nonmonetary phenomenon. The Congress and the administration, public opinion, and most of the economics profession supported that policy. The result was inflation. That inflation eventually led to the present consensus that the control of inflation is the paramount responsibility of the central bank.

The post-Volcker Hetzel, studying the pre-Volcker Burns, shows in striking contrast the evolution of economic thought regarding everything that is cost-push.

Samuelson and Solow in 1960 evaluate economic conditions as well as cost-push stories, and even touch on what is today called "conflict" inflation:

But again in 1955-58, it showed itself despite the fact that in a good deal of this period there seemed little evidence of overall high employment and excess demand. Some holders of this view attribute the push to wage boosts engineered unilaterally by strong unions. But others give as much or more weight to the cooperative action of all sellers ... who raise prices and costs in an attempt by each to maintain or raise his share of national income, and who, among themselves, by trying to get more than 100 percent of the available output, create seller's inflation.

There is no reference here to supply shocks, though there is rudimentary reference to supply-side inflation.

Charles L. Schultze in 1959 offered economic analysis:

7. The largest part of the rise in total costs between 1955 and 1957 was accounted for not by the increase in wage costs but by the increase in salary and other overhead costs...

8. Overhead costs have been increasing as a proportion of total costs throughout the postwar period. This has intensified the downward rigidities in the cost structure of most industries...

11. Since it does not stem primarily from aggregate excess demand, but largely from excess demand in particular sectors of the economy, a slow increase in prices cannot be controlled by general monetary and fiscal policy if full employment is to be maintained...

No indication here, either, of "shocks" in this primordial thinking. And, perhaps surprisingly, there is less concern with wages than with other business costs. Like Burns in the early 1970s, Schultze in the late 1950s was in search of the cause of cost-push inflation.

Note in overview that the older analyses of

cost-push are much more thorough and detailed than the newer commentary like

Sumner's or Welker's. Note also the search, the change in importance of the search for the source of cost-push pressure.

Before Volcker, the economist's task was to search for the underlying cost driving cost-push inflation. After Volcker, the economist's task was to assert the supremacy of supply and demand, the quantity of money, the price of credit, and the primary mission of maintaining low inflation -- and to hell with cost pressure.

Sunday, March 14, 2021

Terms of the Times (1): In the Keynesian era, cost-push "attracted widespread attention"

... prices started noticeably rising in 1956 and this upward trend continued through to 1960 with a short interruption in 1958. This persistent inflation attracted widespread attention for it was occurring in peacetime and did not seem to fit the traditional explanations of general price movements. The government and Congress actively engaged in the resultant debate...

An ngram comparing the terms "supply shock" and "cost-push":

The ngram for the word "inflation"

peaks in 1978 and, like inflation itself, drops rapidly after 1980. For

me, the rate of inflation explains why the blue curve here never goes

as high as the red. Changes in the rate of inflation also may help explain why red goes down so much

farther than blue goes up between 1970 and 2000, the low level of both

thereafter, and the decline of both after 2010.

It is certainly easy to see the huge focus on "cost-push" between the second World War and the first Oil Crisis. Is it bigger than you thought? It is far bigger than I thought. But the whole concept of cost-push inflation has been pretty well extinguished from modern thought.

Years ago now, Nick Rowe commented at Josh Hendrickson's Nominal Income and the Great Moderation. Nick quoted Hendrickson:

Josh: “Rather, the view of Burns and others was that inflation was largely a cost-push phenomenon...”and replied:

People forget (and maybe younger people never knew) just how common that view was in the 1970’s. It was common among economists as well as the general population. It was almost the orthodoxy of the time, IIRC.

"... maybe younger people never knew..."

Yes, the whole concept of cost-push inflation has been pretty well

extinguished from modern thought. But as you can see in the ngram above,

from 1967 to 1980 (check my work) the term "cost-push" was used more than twice as often as the term "supply shock" has ever been used. What remains of cost-push has been removed from the lexicon -- and from modern thought -- by the change in terminology.

The whole concept of cost-push inflation has been pretty well extinguished from modern thought. That would be okay if there was no such thing as cost push inflation. It would be okay if there was no possibility that rising cost will cause a slowing of economic growth unless the cost pressure is relieved by inflation.

In other words, the whole long-term problem of declining economic growth could be due to cost pressure that we overlook because we took the "cost-push" concept and flushed it down the toilet.

Saturday, March 13, 2021

I got my second shot yesterday

My wife patrolled the internet early in the day, couple months ago, and got me covid vaccination appointments at CVS. First time I ever felt lucky to be "65 and over".

First shot February 12

Second shot March 12

After

my first shot they gave me a little white card on which they had

written my name, "Moderna" and a lot number, the date and location.

Second shot, they updated the card. On the card it says "Bring this

vaccination record to every vaccination or medical visit..."

Only reaction I had to the first shot: That first night, I couldn't sleep.

To the second shot, too early to say. So far, no reaction. Just relief.

I want to add that the topic ("vaccination") being the same in today's post and yesterday's is just coincidence. But it also strikes me as a sign of real progress. And that's a good feeling.

Friday, March 12, 2021

Thursday, March 11, 2021

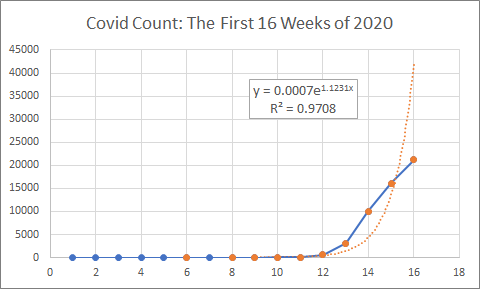

Sixteen weeks

|

| Source: 3News, November 17 2020 |

Exponential growth?

In the neighborhood of exponential, yeah.

Excel wouldn't let me add the exponential trendline until I eliminated the zero values.

The trendline is based on the orange (non-zero) dots.

//

Covid Deaths by week for 2020. I want to leave out the word "deaths" so as not to emphasize the unpleasantness of the topic. Every other week shown:

| Week 6: | 1 |

| Week 8: | 5 |

| Week 10: | 35 |

| Week 12: | 571 |

| Week 14: | 10,012 |

| Week 16: | 17,067 |

What makes a series of numbers "exponential" is that it doubles at regular intervals, every week or every year, for example.

Suppose the Covid number doubles every week, and starts at Week 6 with one death. Then we expect two in week 7 and four in week 8. Four is close to the reported count of 5, so our guess, and the reported number, seem reasonable.

No deaths were reported in Week 7. Does that seem odd? I don't think so. An exponential sequence of numbers is only an estimate or prediction, at least as I use it here. Anyway, zero is pretty close to 2.

Starting with one in Week 6 and doubling weekly, we see four in Week 8, eight in week 9, and 16 in Week 10. Deaths reported for Week 10 were 35, more than twice our estimate of 16. Let's go with the reported number.

Our estimate: 35 in Week 10, 70 in Week 11, 140 in Week 12. The reported number for Week 12 is 571. Our estimate is way low. It is likely that our "weekly doubling" assumption is incorrect. It is also possible that the arithmetic requires unrealistic counts (unrealistic, like 1.8 deaths, say).

It is also possible that the reported numbers are incorrect. Certainly the reports could be based on the best information available (and I assume they are) and entered and checked carefully (and I assume they are) and still differ from "God's count". And sometimes people do mess with the numbers for their own reasons, or tally the numbers their own way for whatever reason. But dead is dead, and that's not an easy thing to hide. I trust the reported numbers, same as I do with economic data.

Let's revise our estimate. Let's say the 35 deaths reported in Week 10 is correct. The Week 12 number is 571. How many doublings does it take to get from 35 to 571?

35 ... 70 ... 140 ... 280 ... 560

560 is close to 571. It takes four doublings to get there. Four doublings in two weeks. So in these weeks it appears that the "doubling time" of the exponential process is about 3½ days rather than a week.

How about going from Week 12 to Week 14? From 571 to 10,012?

571 ... 1142 ... 2284 ... 4568 ... 9136

Four doublings gets us in the neighborhood of 10,012. Five would get us to 18,272 and that's way above the reported number. Four doublings, then, for weeks 12 to 14, the same as for weeks 10 to 12. So my confidence in that doubling time improves.

For the first few weeks we used a 7-day doubling time. Then for the next few weeks the doubling time looks more like 3.5 days. What happened?

Could be that Covid deaths were under-reported in the early weeks, when people were still learning what they were dealing with. That seems realistic to me. That, and the early numbers were so very small that if they're off just a little, the error is still a big percentage. But then, when you get to the bigger numbers and higher death counts, the same (big percentage) error is much easier to see.

Or it could be that the easily-transmitted virus mutated and became even more easily transmitted. This could account for it, and again it could have been missed in the early days, but this explanation seems less "occam" simple. Besides, there was no talk of mutation in the early days of the pandemic. Also, it seems that this possibility could be checked by comparing concurrent data from other nations. Seems to me if mutation in the early weeks reduced the doubling time, we'd have heard about it by now.

Could be that I made a sloppy guess and didn't check it enough. I think that's what happened.

I should say, I'm no expert. I just find it interesting to look at numbers and think about how they came to be. And evidently, I have more thoughts on this topic than I realized.

If I miss anything that seems to you worth mentioning, don't hesitate to mention it.

From Week 14 to Week 16, the reported numbers don't even double once. We jump from 10 thousand to 17 thousand deaths in that two week period. Based on the reported numbers, the "rule of 70" gives me a doubling time of 16.7 days. When I try to figure it I get 17.9 days. Either way, about 2½ weeks. That's the slowest doubling time so far, slower even than in the first few weeks. What happened?

I think the slower doubling time -- the slower spread of Covid -- came about because we learned how to deal with the problem: the hand-washing, the social distancing, and, you know, shutting down the economy and wearing masks.

//

The first US death from Covid was on Thursday, February 6, the sixth Thursday of the year. Week six.

On Wednesday, March 11, the NBA suspended game play until further notice. Week 11.

According to AJMC, on March 13, the Trump administration declared Covid 19 a national emergency and issued a travel ban. Assuming that the first Saturday of the year is the end of the first week of the year, Friday, March 13 was in Week 11.

On March 19, California became the first state to issue a stay-at-home order. Week 12. [AJMC]

On March 25, "Mathematical models based on social distancing measures implemented in Wuhan, China, show keeping tighter measures in place for longer periods of time can flatten the COVID-19 curve." Week 13. [AJMC]

On April 16, "After Trump briefly entertains the idea of reopening the US economy in time for Easter Sunday, the White House releases broad guidelines for how people could return to work, to church, and to restaurants and other venues. The plan outlines the concept of “gating criteria,” which call for states or metropolitan areas to achieve benchmarks in reducing COVID-19 cases or deaths before taking the next step toward reopening." Week 16. [AJMC]

Wikipedia lists 23 states that lifted stay-at-home orders or advisories between April 26 (Week 18) and June 11 (Week 24).

Wednesday, March 10, 2021

Past tense

An "IMF Staff Position Note" dated 12 Feb 2010: Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy by Olivier Blanchard, Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, and Paolo Mauro. (PDF, 19 pages)

I thought the table of contents was interesting, in particular headings II thru IV:

I got to page 7 before I had to stop reading and start writing.

The "What We Thought We Knew" section is all past tense:

- Stable and low inflation was presented as the primary, if not exclusive, mandate of central banks...

- There was an increasing consensus that inflation should not only be stable, but very low...

- Monetary policy increasingly focused on the use of one instrument, the policy interest rate...

and so on, until we come to "The Great Moderation". Here, the text starts in the past tense:

- Increased confidence that a coherent macro framework had been achieved was surely reinforced by the “Great moderation,”...

Halfway into it, however, they offer their current support for past analysis:

But the reaction of advanced economies to largely similar oil price increases in the 1970s and the 2000s supports the improved-policy view. Evidence suggests that more solid anchoring of inflation expectations, plausibly due to clearer signals and behavior by central banks, played an important role in reducing the effects of these shocks on the economy.

I thought that was funny. In context, the change in perspective stands out sharply -- unless you still support the past analysis, perhaps. But if you start your story by saying

The crisis clearly forces us to question our earlier assessment.

then you ought to follow Descartes and doubt everything. You don't get to keep the parts you like and rebuild from there. That's not how it works. Science is a method.

Tuesday, March 9, 2021

Broad Money as a Multiple of Base Money in the UK since 1844

A measure of how far "base money" has been stretched, or how many

times interest is paid to somebody, somewhere, per Pound of base money:

|

| Graph #1 |

At an interest rate of, say, 3%, from 1885 to 1965 it would take about 12% of base money each year, to pay the interest on the money created on top of base money.

At the same hypothetical interest rate, from 1990 to 2005 it would take about 72% of base money each year to pay the interest on the money created on top of base money.

But if the UK is anything like the US, there is more debt than what's included in broad money on this graph. Positive Money, some years back, was saying "Banks create new money whenever they make loans. 97% of the money in the economy today is created by banks, whilst just 3% is created by the government."

97 divided by 3 is 32.333... times 3% is 97%. At an interest rate of 3% it would take 97% of the base money each year, to pay the interest.

The graph, by the way, doesn't go up to 32.333. It only goes up to 30.

Adam Smith said

Let us suppose, for example, that the whole circulating money of some particular country amounted, at a particular time, to one million sterling, that sum being then sufficient for circulating the whole annual produce of their land and labour. Let us suppose, too, that some time thereafter, different banks and bankers issued promissory notes, payable to the bearer, to the extent of one million, reserving in their different coffers two hundred thousand pounds for answering occasional demands. There would remain, therefore, in circulation, eight hundred thousand pounds in gold and silver, and a million of bank notes...

But a million pounds is sufficient, Smith says. Long story short, the circulating money settles back down to one million pounds paper, with the gold and silver gone to uses other than circulation.

I don't see base money in Smith's example. But at 3% interest, the cost of this million pounds of paper money would be 3% of the money he started with. Not 12%, or 72%, or 94%, but 3%. That's low-cost finance. It would mean less financial cost embedded in output, and less in the cost of living.

//

Bank of England, Broad Money in the United Kingdom [MSBMUKA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MSBMUKA, March 8, 2021.

divided by

Bank of England, Monetary Base M0 in the United Kingdom [MBM0UKA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MBM0UKA, March 8, 2021.

-

I'm not a fan of "diagrams" in economics, but sometimes... This is a screen capture of slide 36 from a SlideShare presentatio...

-

In the Google News this morning, "The Fed may have saved the economy by hiking rates for 18 months—and may have guaranteed crisis for...

-

Bosch season five air date: 18 April. Ten episodes. Four days later, six of the transcripts were already available. A few days later, the ...

-

JW Mason : "... in retrospect it is clear that we should have been talking about big new public spending programs to boost demand.&quo...

-

Comparing the labor cost of Nonfinancial Corporate Business (NCB) to NCB profits since 2018. The vertical gray bar during 2020 shows the re...