From Gallup: "No Recovery: An Analysis of Long-Term U.S. Productivity Decline". Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup Senior Economist.

https://news.gallup.com/reports/198776/no-recovery-analysis-long-term-productivity-decline.aspx

Hey,

the Gallup PDF includes a graph showing long-term economic decline,

right there on the cover. I'm big on long-term economic decline, so I

can't help but like the paper.

Gallup asks: "Why is growth down?" They summarize several different explanations and say "There is no consensus among economists or other experts as to why growth has slowed."

Gallup concludes: "Political forces, not technical or scientific ones, are now the chief restraints on growth." This is what happens when economic theory incorrectly explains the economy, and economic problems become everyone's problem: People start to think the problem is political. Yet, in truth, there is no remedy except to throw over the axiom of parallels and to work out a non-Euclidean geometry. The problem is not political. It is an economic problem with an economic solution.

Under the heading "The Key Sectors Dragging Down Growth" we read:

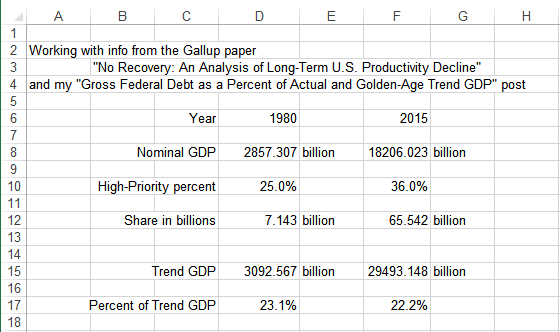

Here, the focus is on the key period between 1980 and 2015 when the slowdown in GDP growth per capita began. Over this period, private and public spending on housing, healthcare and education soared, and these sectors absorbed a larger share of GDP, going from an already substantial 25% to an enormous 36%. Of these, healthcare saw the largest jump, increasing from 9% to 18%.

Between 1980 and 2015, housing increased one percentage point, from 10% to 11% of GDP. Education increased by one percentage point, from 6% to 7%. Healthcare doubled, from 9% to 18% of GDP.

These sectors where spending increased as a percent of GDP, I'm calling them high-spending sectors. I was going to call them "high-priority" sectors, but that seems to contradict the Gallup paper. They emphasize that the high-spending sectors reflect not only "a shift in spending" away from other sectors, but also increasing prices. This is effective writing:

The Bureau of Economic Analysis produces price indexes by industry, and these price indexes show rapidly escalating prices. Education is 8.9 times more expensive in 2015 than in 1980. Within education, higher education specifically is 11.1 times more expensive. Healthcare costs 4.8 times more than it did in 1980, medical insurance costs 8.7 times more and housing 3.5 times more. Thus, the shift in spending toward education, healthcare and housing cannot only reflect increased demand...

Yeowza!

The cost of Gallup's high-spending categories increased from 25% of GDP in 1980 to 36% in 2015. But notice that they show their high numbers relative to GDP -- and GDP growth is slow. So I have to ask: How much of this apparent increase in the high-spending is really due to the slowdown of GDP growth?

All of it!

Using the same "Golden Age trend" values I used for my recent federal-debt-to-GDP post, the high-spend number for 1980 drops from 25% of GDP to 23.1%. For 2015 the number drops from 36% to 22.2%. If GDP growth had continued at its 1946-1974 rate, our spending on healthcare, housing, and education would have been a smaller percentage of GDP in 2015 than it was in 1980! The big change is the slowdown in GDP, not the increase in healthcare, housing, and education.

This

should give you an idea how serious the long-term economic decline is. But economists don't even talk about it. They tell "long boom" stories instead.

Let me go back to that quote about the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the "rapidly escalating prices". I'll start where I left off:

... Thus, the shift in spending toward education, healthcare and housing cannot only reflect increased demand. At a per-unit level, prices have also increased, driving up the share of spending on these products. This suggests that something is holding back supply.

Something is holding back supply.

The phrase "something is holding back supply" is code for "cost-push" inflation. The combination of reduced supply, slowing growth, and rising prices indicates that there is cost pressure driving the inflation. Or, you know, to keep the "there's no such thing" people happy, the answer to the question "Why is growth down?" is cost pressure. The Federal Reserve finds itself having to "print too much money" to get the little economic growth that it gets, and it has targeted "two percent inflation" to prevent outright economic decline.

Prices are being "forced up", as Henry Hazlitt said, to the point that "they force an increase in the money

supply." Hazlitt's words. That's Hazlitt's words. Hazlitt, for the "no such thing as cost-push inflation" people.

Despite

all the inflation we've had, economic growth is still slow and still

getting slower. I call it long-term decline. So does Gallup. And come to think of it, John Cochrane worries about long-term decline, too. And since it's not just me, this at least hints at how serious the cost

pressure problem is.

Oh, and by the way: The cost pressure arises from the growth of finance. We can reduce the cost pressure, reduce inflation, and improve growth by reducing the accumulation of private-sector debt until prosperity emerges.

Or we can wait it out and become living proof that civilizations die by suicide.

.png)

.png)